History of The Northwest Art Project

Written by:

Dee Dickinson, Founder of the Northwest Art Project (1960); Active Member (1953 to 1979); Sustainer (1980 to Present)

Tricia Tiano, Sustainer Advisor Emeritus (2013-Present); Active The Northwest Art Project Committee Member (1987 to 2013)

This is the story of how and why it was possible for 300,000 children to learn how to understand and appreciate the visual arts through The Northwest Art Project, the longest-lasting project of the Junior League of Seattle.

In the late fifties, Sputnik went up, and the boom came down on public education, bringing in an intense focus on improving math and science skills but also, in the process, cutting budgets in the arts. In fact, it seems that since then whenever public school budgets are cut, the arts are the first to go. Yet in every culture since the beginning of human history, the arts have been essential parts of daily life, decorating cave walls and early tools and utensils. The arts have been the high point of every civilization. Furthermore, they have always been essential components of the finest educational systems, not just because they have cultural value, but also because they are languages that all people speak.

In the early 1960s, the Junior League’s Community Arts Committee was concerned about the lack of arts education in public schools and created The Northwest Art Project to restore some of what was being lost.

School halls were often dingy and on the walls were only faded reproductions here and there. Dee Dickinson, chair of the committee at that time, was aware that the Northwest was an unusually rich source of visual art by local artists who were already gaining worldwide acclaim. She was also painfully aware that there were many children who had never seen an original work of art and had never visited an art museum. There was, as a result, a real void in their education that might be filled by learning to understand and appreciate the artistry and have opportunities to do creative work of their own through the guidance of trained docents.

A concerted effort for community buy-in began to unfold …

Dee first approached Dr. Richard Fuller, Seattle Art Museum’s Director, about her idea of bringing original objects to schools but soon learned that it was not aligned with the Museum’s mission at the time.

She next approached Kenneth Callahan, who was wildly enthusiastic about the proposed project. He said, “Come with me.” They went upstairs to a guest room, and he pulled out from under the bed two magnificent paintings that he said he had been saving for a major museum collection. He said, “Take your pick. Let the children come close to see it well. Let them touch it and feel it and smell it. If it gets dirty bring it back to me and I’ll clean it off with a raw potato. Encourage them to look at it carefully and tell what they think it means!!” That visit launched the project, and Callahan’s magnificent painting, “Crystalline World,” led it off.

A small jury was created composed of professional art experts including Junior League member Virginia Wright, a well-known collector of art. They counseled the committee on which artists to add and they next approached Guy Anderson, Paul Horiuchi, George Tsutakawa, James Washington Jr., Spencer Moseley, and Glen Alps. Later, through a Junior League grant, paintings by Mark Tobey and Morris Graves were added, and a painting by Helmi Juvonen was acquired by sending art materials to the hospital where she was a patient.

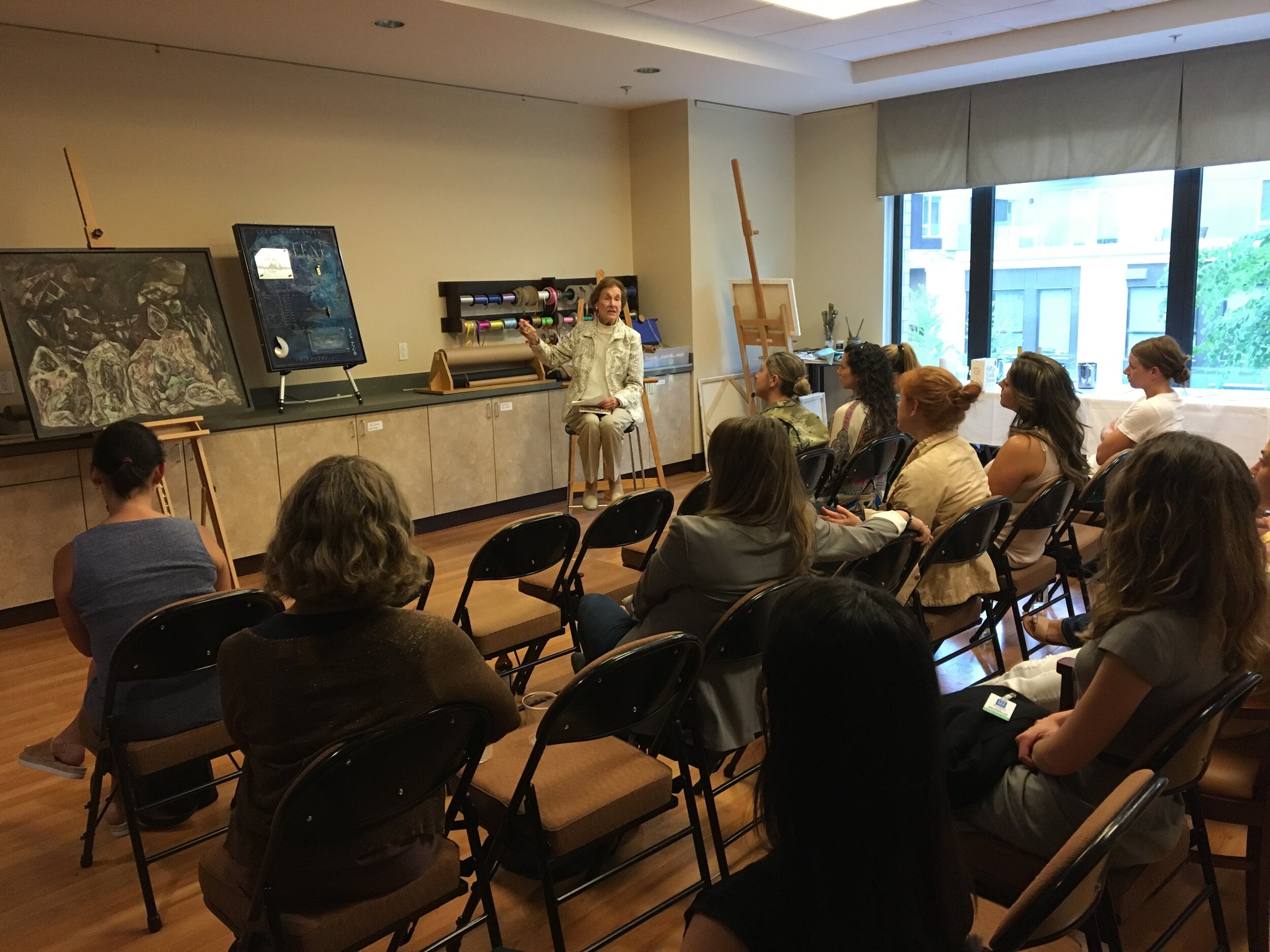

It is always a special treat to attend a docent training that is joined by Dee Dickinson, founder of The Northwest Art Project.

The project was planned to be taken into the schools by Junior League docents who were trained in how to make their visits interactive, not just informational, and a number of different trainers, artists, and visits to studios have been involved over the years.

As a result, the docents have helped children to see with fresh eyes, looking for hidden meanings, appreciating the colors and designs, learning about the use of different media, responding with their own views of the artworks, and being inspired to create some works of their own. The visits often become multisensory experiences as children imagine walking into a painting, hearing, feeling, or smelling what it is like inside. At times the music is used to blend with the rhythms of a painting, or children are asked to make sounds like those of the animals pictured, or to give a work of art a title of their own, or write a short story or poem in response to what they see. The works of art are left at the schools for several weeks so that further exploration and inspiration may occur.

Initially, the League docents received their training at the Seattle Art Museum, and later at the Henry Art Gallery on the University of Washington campus where they learned about art principles and studied art history. The artworks in the League’s collection were kept at the Henry Gallery when they were not in use in the schools. At that time, the docents themselves would take some of the artworks to the different schools in their own cars. As the collection grew, however, crates were built and storage and transportation were arranged. Later on, the training sessions and storage moved to the League office in Madison Park. As the collection continued to expand, more space and controlled temperature in the environment were required, so the artworks were transferred to Artech which cared for them when they were not traveling. The crates are now stored at the Junior League office and Mirabella, where Dee Dickinson resides. As of 2020, there are 10 crates, 7 of high travel throughout the schools. In 1994, a relationship began with the Bellevue Arts Museum, and during that time the Junior League docents offered training on how to present the artworks interactively to educators and PTA parents on the Eastside. This connection extended the reach of the project. Also, since 2001, a professional art education consultant, Halinka Wodzicki, has helped enlarge the scope of the docent and teacher training. She has written extended learning lesson packets that are given to the teachers to help them connect the children’s art experiences to their curriculums.

A long-standing legacy of preserving art education in King County Schools.

During the last 60+ years, over 500 Junior League docents have been part of the project that has reached over 300,000 children in more than 600 schools in King County. In 2004, The Northwest Art Project was displayed at Harborview Medical Center; however, in 2010, the entire collection, which by then, included 75 works of art, was displayed for the first time in a museum setting at the Bellevue Arts Museum.

Docents have reported numerous rewarding results of their visits to the schools. During one visit, an autistic child who had never before spoken in class talked eagerly about a painting he had fallen in love with, and after that, he continued to participate more frequently in class discussions. One student was fascinated by Jack Chevalier’s mixed-media piece, “Lighthouse,” and said she would like to have it for her own because it would help her with her math. In another class, one of the students was so inspired that he continued working on his own painting and missed lunch in the process. In an English as a Second Language class, a docent asked the children what they thought the people were anticipating in Joe Max Emminger’s “Two People Waiting.” One student answered “Freedom” which led to a rich discussion of expectations and experiences one has in coming to a new country. Children are so often stimulated that they are still anxious to give their interpretations of the art when the period ends. Children’s eager participation, thoughtful interpretations, artworks, poems, stories, dances, and dramatizations continue to surprise not only the docents but also the children’s own teachers.

Presently, the Junior League’s Northwest Art Project includes not only paintings and drawings but also collages, sculptures, glass art, photography and carvings. There are 81 pieces, 79 of which are divided among 10 exhibits that make up the traveling collection. It continues to meet the needs that motivated its inception. Public schools still face budget cuts in the arts, and there are often fewer opportunities to develop higher-order thinking skills, applied learning, and seeing projects through from beginning to end. These skills are in great demand today as any kind of employment and even daily living require more creative thinking and problem-solving abilities. Studies (as reported in the media such as the July 17, 2010 issue of Newsweek) have shown that creativity has been declining in our country at the same time as creative thinking is being emphasized in the schools and is rising in the workplaces of other countries. Even the U.S. Patent Office is concerned.

Another current need in education, as diversity increases in school populations, is for a greater variety of teaching and learning styles that teachers often learn through observing the docents’ visits. Many teachers are able to integrate what they have observed into other parts of the curriculum as well, resulting in their students’ greater understanding and ability to apply what they have learned. The Northwest Art Project continues to seek ways to fill some of today’s needs as well as those in the years ahead to help in the development of “whole” human beings, mentally, physically, and emotionally.

Note: This timeline was updated in January 2021.

How has The Northwest Art Project impacted you?

Do you have a story to share about participating in our curriculum when you were a student? Did your art docent training influence how you now view art? Are you a parent of a student who participated in one of our curriculums with a story to tell? Over the years people from all stages and walks of life have been a part of The Northwest Art Project and this is our way of building a virtual community to share those stories.

Note: Your last name and email address will not be shared or posted.